David Katz, founder and CEO of Plastic Bank, returned to talk with Mitch Ratcliffe about…

The post Best of Earth911 Podcast: Plastic Bank’s David Katz On Building A Global Bottle Deposit System appeared first on Earth911.

David Katz, founder and CEO of Plastic Bank, returned to talk with Mitch Ratcliffe about…

The post Best of Earth911 Podcast: Plastic Bank’s David Katz On Building A Global Bottle Deposit System appeared first on Earth911.

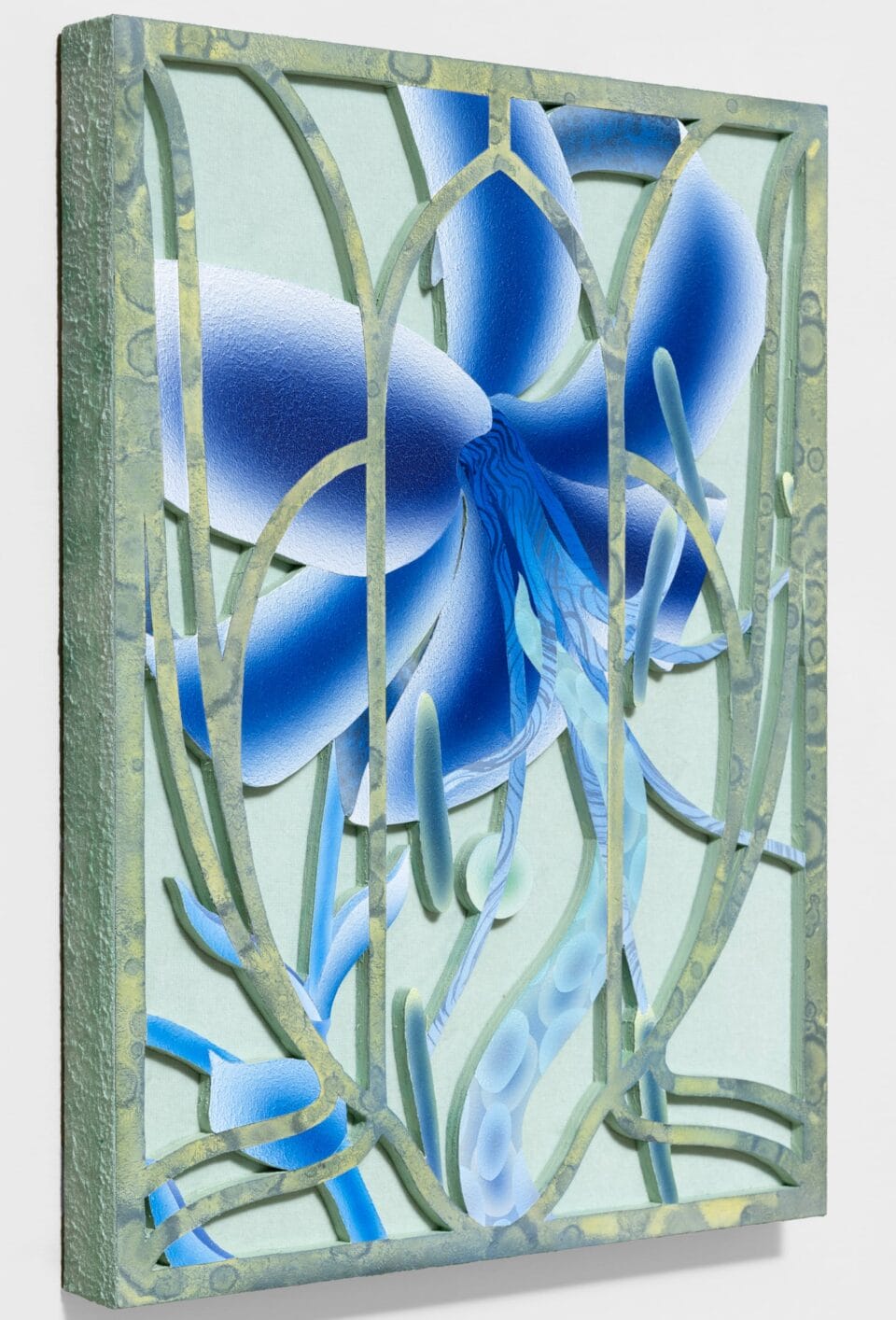

Behind barred motifs evocative of a wrought iron fence, otherworldly flowers are in full bloom, their heads stretching wide and tall while tendrils and leafy vines wind around the open barriers. Rendered in contrasting palettes of jewel tones and pale, muted hues, these uncanny plants are part of the latest body of work by Mevlana Lipp.

While visiting Venice earlier this year, the Cologne-based artist admired the elaborately patterned fencing that wove its way throughout the historic islands. “As I wandered through the city, I noticed the intricate metal bars on many windows,” he says. “For me, these bars symbolize a barrier between the world I inhabit and the fictional place I long for.”

Vista is the culmination of this inspiration and presents an electrifying botanical collection. For these pieces, Lipp continues to meld painting and sculpture, as he layers acrylic paint, ink, and sand onto intricately cut wooden panels, which he positions atop velvet. This soft material interacts with the mottled, spotted, and patterned textures of the painted components and bolsters the sense of depth, becoming a vast chasm behind the fantastical florals.

Compared to his previous works, though, Vista ventures into warmer, brighter color palettes. The artist shares:

While the dark blue, green, and lilac backgrounds often create a sense of infinite voids, I wanted to explore other imageries as well. Think of an icy cold mist or a red desert stretching endlessly into the distance. I wanted to create works which have a wider array of temperatures.

Lipp’s interest in expanding his palette dovetails with the symbolic elements of his work. As the artist sees it, plants are metaphors for base instincts and emotion, as they commune with each other and various species without the same social and cultural pressures of humans. Broadening his formal approach offers more room for spontaneity and unrestrained exchanges. “When you walk into the forest, you take a look at all the existing connections, at how things interact with each other without fear,” he says. “Plants don’t run the risk of hurting each other’s feelings.”

Vista is on view through December 15 at Capsule Venice. Find more from Lipp on Instagram.

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $7 per month. The article Fantastic Blooms Entwine with Sculptural Motifs in Mevlana Lipp’s Imagined World appeared first on Colossal.

Behind barred motifs evocative of a wrought iron fence, otherworldly flowers are in full bloom, their heads stretching wide and tall while tendrils and leafy vines wind around the open barriers. Rendered in contrasting palettes of jewel tones and pale, muted hues, these uncanny plants are part of the latest body of work by Mevlana Lipp.

While visiting Venice earlier this year, the Cologne-based artist admired the elaborately patterned fencing that wove its way throughout the historic islands. “As I wandered through the city, I noticed the intricate metal bars on many windows,” he says. “For me, these bars symbolize a barrier between the world I inhabit and the fictional place I long for.”

Vista is the culmination of this inspiration and presents an electrifying botanical collection. For these pieces, Lipp continues to meld painting and sculpture, as he layers acrylic paint, ink, and sand onto intricately cut wooden panels, which he positions atop velvet. This soft material interacts with the mottled, spotted, and patterned textures of the painted components and bolsters the sense of depth, becoming a vast chasm behind the fantastical florals.

Compared to his previous works, though, Vista ventures into warmer, brighter color palettes. The artist shares:

While the dark blue, green, and lilac backgrounds often create a sense of infinite voids, I wanted to explore other imageries as well. Think of an icy cold mist or a red desert stretching endlessly into the distance. I wanted to create works which have a wider array of temperatures.

Lipp’s interest in expanding his palette dovetails with the symbolic elements of his work. As the artist sees it, plants are metaphors for base instincts and emotion, as they commune with each other and various species without the same social and cultural pressures of humans. Broadening his formal approach offers more room for spontaneity and unrestrained exchanges. “When you walk into the forest, you take a look at all the existing connections, at how things interact with each other without fear,” he says. “Plants don’t run the risk of hurting each other’s feelings.”

Vista is on view through December 15 at Capsule Venice. Find more from Lipp on Instagram.

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $7 per month. The article Fantastic Blooms Entwine with Sculptural Motifs in Mevlana Lipp’s Imagined World appeared first on Colossal.

When e-cigarettes, or vapes, came on the market in 2007, they were initially seen as…

The post Recycling Mystery: Vapes and Vaping Products appeared first on Earth911.

When China’s plastic ban took effect in January 2018, recycling centers in Boise, Idaho, were…

The post Hefty ReNew Program: Still Working to Keep Plastics Out of Landfills appeared first on Earth911.

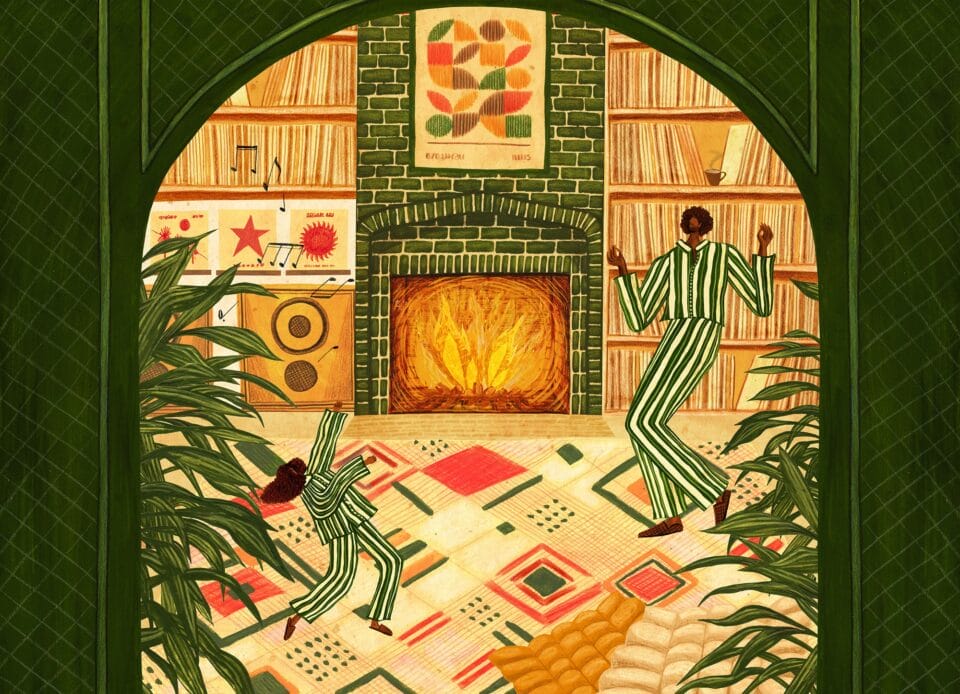

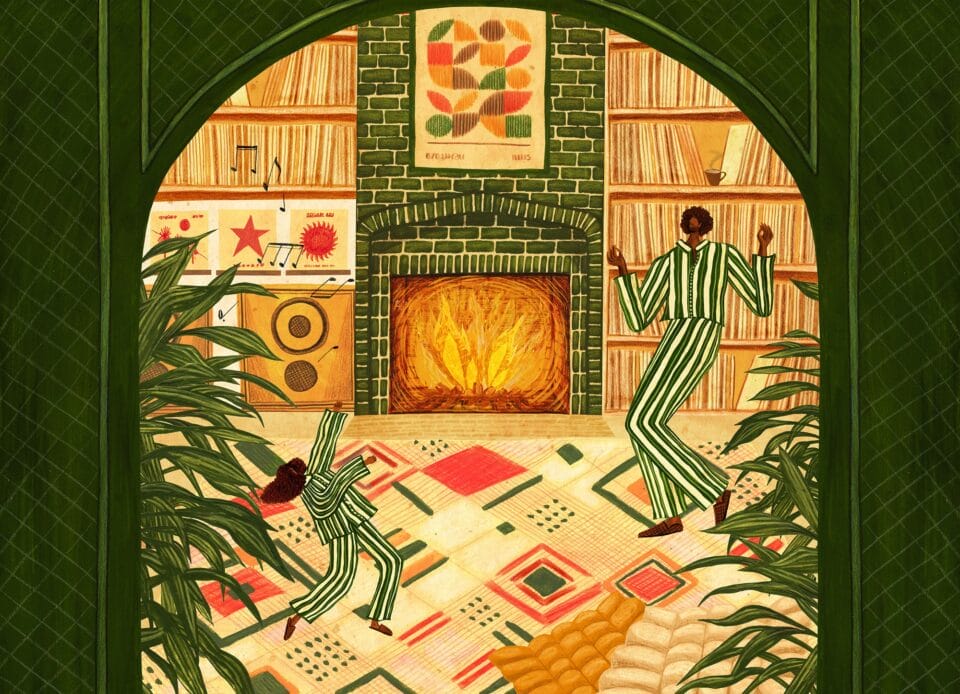

Swathed in patterned coats, overlooking expansive vistas, or reveling the joys of solitude, the characters in Rosanna Tasker’s illustrations (previously) delight in simple pleasures. Emphasizing the potential of color and contrast to create a sense of warmth and depth, figures bask in glowing interiors, and landscapes fade into the blue of distance.

Tasker’s figures are often camouflaged or miniaturized by their towering surroundings, whether wandering among stacks of textiles or strolling through a grove of trees. “Recently, I’ve been enjoying playing with pattern, light and depth,” she tells Colossal. “I’m always aiming for the balance of challenging my comfort zone while also staying true to my natural style.”

While she can’t yet divulge some of the exciting projects in the works for the coming year, Tasker is currently working on another illustration for Singing Holidays, which plans music-focused tours around Europe and elsewhere.

She enjoys working with clients that provide open briefs and lend their full trust. For example, Singing Holidays gives her “the space to really experiment with my work and create images that are mostly self initiated, while still having some parameters or starting points to work within—which is my favourite type of commission and when I feel most creative,” she says.

Prints and calendars are available in Tasker’s online shop, and you can explore more work on both her website and Instagram.

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $7 per month. The article Wonder and Warmth Emanate from Rosanna Tasker’s Vivid Illustrations appeared first on Colossal.

Swathed in patterned coats, overlooking expansive vistas, or reveling the joys of solitude, the characters in Rosanna Tasker’s illustrations (previously) delight in simple pleasures. Emphasizing the potential of color and contrast to create a sense of warmth and depth, figures bask in glowing interiors, and landscapes fade into the blue of distance.

Tasker’s figures are often camouflaged or miniaturized by their towering surroundings, whether wandering among stacks of textiles or strolling through a grove of trees. “Recently, I’ve been enjoying playing with pattern, light and depth,” she tells Colossal. “I’m always aiming for the balance of challenging my comfort zone while also staying true to my natural style.”

While she can’t yet divulge some of the exciting projects in the works for the coming year, Tasker is currently working on another illustration for Singing Holidays, which plans music-focused tours around Europe and elsewhere.

She enjoys working with clients that provide open briefs and lend their full trust. For example, Singing Holidays gives her “the space to really experiment with my work and create images that are mostly self initiated, while still having some parameters or starting points to work within—which is my favourite type of commission and when I feel most creative,” she says.

Prints and calendars are available in Tasker’s online shop, and you can explore more work on both her website and Instagram.

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $7 per month. The article Wonder and Warmth Emanate from Rosanna Tasker’s Vivid Illustrations appeared first on Colossal.

With its bulbous shape and a canopy that resembles an upside-down root system, the baobab tree is an iconic symbol of the African continent. Its origins are also the stuff of legend…literally. Along the Zambezi River, some tribes believed that one day their gods became angry, ripped the baobab from the ground, and tossed it up into the air, resulting in its inverted-like appearance. In another tale, God gifted the baobab to a hyena. However, the hyena felt so repelled by the tree’s already unusual exterior, he shoved it to the ground upturned.

© Justin Jin / WWF France

Whatever way the baobab came to be, it’s undoubtedly a remarkable specimen. Baobabs can grow up to 100 feet tall, have a circumference of as much as 165 feet, and live as long as 3,000 years. These solitary trees are also incredibly resilient, thriving in dry, open areas such as the savannas of southern Africa and western Madagascar, and surviving by storing water in their massive trunks.

Their thick bark protects them from bushfires, while their massive root systems help slow soil erosion and aid in the recycling of nutrients. Baobabs may depend on pollinators like fruit bats and bush babies to reproduce, but the trees themselves are incredibly regenerative. They can even create new bark when needed, healing wounds that would take other trees down.

Then there’s the baobab’s fruit: a woody round or egg-shaped pod that can grow up to a foot long and hangs from the tree’s branches courtesy of a long, thick stalk. Its pulpy interior is loaded with seeds and brimming with nutrients, including tartaric acid—a natural antioxidant—and loads of Vitamin C.

© James Morgan / WWF-US

Native to sub-Saharan Africa, the southern Arabian Peninsula (Yemen, Oman), and Australia, baobabs consist of 9 species. While the African continent is home to two different kinds, six are endemic to Madagascar, and Australia has one type of baobab. The latter is commonly known as the ‘boab’ among Aussies and thrives in both Western Australia’s Kimberly region and the country’s Northern Territory.

Baobab trees are nicknamed “The Tree of Life,” and for good reason. Between just the bark and fruit alone, baobabs offer more than 300 vital uses. While elephants quench their thirst on the tree’s water-rich interior, they also snack on its produce and then fertilize the local soil through their droppings. Baboons crack open the fruit’s hard exterior and fill up on its pulpy seeds (leading to the baobab’s other moniker, the ‘monkey bread tree’).

Marabou storks and red-billed buffalo weavers nest in their branches, and fruit bats and bush babies—as well as lemurs in Madagascar—sip up the nectar from their blossoms, pollinating one flower to the next as it goes. These large white blooms spread their petals at night and flower for no more than 24 hours. They typically spring to life during or after the rainy season.

© Justin Jin / WWF France

As much as wildlife depends on the baobab tree (and vice-versa), so do humans. Not only is the fruit’s sour brown pulp edible and nutritious, but soak it in water and it becomes a refreshing drink. People who live around baobab trees will roast and grind its fruits’ seeds to produce a beverage akin to coffee, or boil the tree’s leaves and eat them like spinach. Not only are these leaves loaded with potassium and magnesium, but they’re often used in traditional medicine for treating ailments such as insect bites and asthma.

The tree’s bark is the basis for everything from paper and cloth to ropes and baskets. People also used it to make waterproof hats and musical instrument strings. By mixing the flower’s pollen with water, you can even create a form of glue.

The older a baobab tree gets, the more impressive it becomes. An ancient Baobab can support an entire ecosystem, from the bees and stick insects that reside among its branches, to the antelope and warthogs that delight in its fruit. In fact, baobabs are considered a keystone species, meaning they play an essential role in local biodiversity.

Despite their enormous size and longevity, baobabs are not immune to threats. Here are just some of the challenges they face (as well as some possible solutions).

Many scientists believe that climate change is killing Africa’s oldest and largest baobab trees, the result of more frequent weather anomalies like floods and lightning storms. Elephants will often damage baobabs during extreme droughts to get to their water supply, sometimes digging into the wood so severely that the tree can simply collapse.

WWF’s assessment of the vulnerability of African elephants regarding climate change shows that their biggest concern is having enough fresh water. Creating safe wildlife corridors is one way to increase an elephant’s source options, and relieve pressure on individual baobab trees in the process.

Madagascar, which is home to six of the world’s 9 baobab species, has experienced massive deforestation, losing approximately 235 thousand hectares of tree cover from 2010 through 2021. This includes the loss of baobab habitats.

WWF’s Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR) in Africa is an initiative helping to restore forests and forest landscapes across 9 African countries, including Madagascar. One action entails working with local communities to develop commercially viable landscape restoration projects, and then connecting these community enterprises with investors and commercial partners so that they can prosper on a larger scale.

© WWF / Martina Lippuner

With their smooth bark, thick, cylindrical trunks, and flat-topped crowns, Grandidier’s baobabs are one of Madagascar’s most recognizable baobab species. It’s also a species that’s highly threatened by the conversion of local forests into agricultural land. Loss of forests can lead to extreme soil erosion, and slash-and-burn farming, as well as over-grazing, inhibit the baobab’s proper regeneration.

WWF’s work in sustainable agriculture includes creating financial incentives, which can help encourage the conservation of biodiversity in places where baobab trees grow.

While the baobab itself is iconic, here are a few that are even more beloved than most.

This especially large baobab in Zambia’s Kafue National Park is known as “the tree that eats maidens.” According to local legend, Kondanamwali fell in love with four beautiful women, who decided that they all wanted human husbands instead. The tree became jealous, so it opened its trunk and pulled the women inside, where they’re said to remain to this day.

More than two dozen towering baobabs line an 853-foot dirt stretch in western Madagascar’s Morondava. In 2007, it became the country’s first “Natural Monument.”

© Justin Jin / WWF France

South Africa’s stoutest baobab is located within Limpopo, the country’s northernmost province, and is recognizable by its humongous trunk and gnarled branches. Although researchers carbon-dated the tree at around 1,200 years old, many residents believe its age is more than twice that. It’s home to a breeding colony of mottled spinetails, a type of bird that’s most common along the West Africa coast.

The post The Baobab Tree: An African Icon and Longtime Legend first appeared on Good Nature Travel Blog.

It was in the early morning when we first spotted Aracy, positioned near a small waterhole in Brazil’s southern Pantanal region. We followed her through the grasslands, watching the jaguar meander among trees and along the occasional dirt pathway—at one point, even walking within several feet of our open-sided 4×4 vehicle—until she spotted a herd of capybaras grazing beside a lake. “Keep quiet,” our guide Lucas whispered. “She’s about to make her move.”

In an instant, the capybaras were running into the water with Aracy sprinting behind them, hoping for an early day feast. Although luck wasn’t on her side this round, the enormous feline put on a show for the ages.

Wildlife is a given in Brazil’s massive Pantanal, a more than 75,000 square-mile UNESCO Biosphere Reserve that’s home to the largest tropical wetlands and flooded grasslands on the planet. Everything from squadrons of peccaries (hoofed mammals that resemble pigs) to alligator-like caiman call this incredible natural region—one that stretches across portions of Brazil, Bolivia and Paraguay, covering an area that’s equivalent to the size of Belgium, Holland, Portugal and Switzerland combined—home.

In fact, the Pantanal hosts South America’s densest concentration of wildlife: we’re talking animals as varied as giant anteaters, musk deer, tapir and blue-and-yellow colored hyacinth macaws. Impressive, since many visitors flock to the continent’s other fauna-filled destinations, like the Amazon rainforest, without knowing that these wetlands exist.

(function(d,u,ac){var s=d.createElement(‘script’);s.type=’text/javascript’;s.src=’https://a.omappapi.com/app/js/api.min.js’;s.async=true;s.dataset.user=u;s.dataset.campaign=ac;d.getElementsByTagName(‘head’)[0].appendChild(s);})(document,123366,’pqjonhkt1vutpsrffqge’);

These days, however, the Pantanal is gaining traction among wildlife lovers, thanks in large part to the efforts of Onçafari, a project established to promote conservation through ecotourism, mainly habituating jaguars to safari vehicles with the notion that the more people see these stealth cats in the wild, the more they’ll likely do something to save them.

> Learn about World Wildlife Fund’s conservation initiatives in Brazil’s Pantanal

© Cassiano “Zapa” Zaniboni

Former Formula 1 racing driver Mario Haberfeld established Onçafari in August 2011. Its name is a combination of “onça,” the Portuguese word for “jaguar,” and “safari,” which means “journey” in Swahili. Haberfeld was inspired to start the project after visiting Africa, where wildlife such as lions, elephants, and hyenas have grown up around safari vehicles.

The Brazil native wanted to bring the same type of ecotourism to the Pantanal, helping to preserve its biodiversity in the process. Although the organization also works with other species ranging from giant otters to crab-eating foxes, in the Pantanal, it’s the jaguars that draw the most attention.

Jaguars are similar to leopards, their African counterparts, though they’re stockier than leopards and more muscular. Each one is also highly unique. Some are more golden in color, their whiskers longer or shorter, and their faces narrower or fuller.

Historically, their range stretches from Argentina north up to Arizona’s Grand Canyon, though their population has decreased by 25% in just over two decades, spurred in large part by deforestation and illegal logging. Today, jaguars occupy less than half of where they once roamed, with sightings only as far north as Mexico’s Sonora state and occasionally crossing the border into Arizona. Seeing one in the wild has long been a remarkably rare experience.

Lucas Morgado is an Onçafari biologist who is well-versed in tracking wildlife. He’s also our safari guide in Brazil’s southern Pantanal. He tells us the story behind Aracy. How she was born back in 2020 and has been in the proximity of vehicles all of her life. She’s the daughter of Isa, one of the first two jaguars to be reintroduced by Onçafari to the Pantanal after losing her mother at a young age. And that she’s missing the tip of her left ear.

©Helder Brandao de Oliveira

We also learn about jaguars in general: things like their having the strongest bite of all cats—even lions and tigers—and how the rosette patterns on their fur are as unique as human fingerprints. And while they’re typically solitary creatures, these elusive cats sometimes form coalitions to survive. Much like us?

Of the estimated 15,000 to 64,000 jaguars remaining in the wild, more than half of them live within the Amazon Rainforest and the Pantanal. About 60 to 80 of these reside inside the 204-square-mile Caiman Ecological Refuge, a renowned private reserve that happens to be the site of our spacious lodge.

Caiman Ecological Refuge is also the site of the Onçafari jaguar team’s scientific research center. Here, the project’s team members constantly evaluate the felines’ health and monitor their behavior through motion sensor cameras, direct observation, and a handful of GPS-equipped radio collars that can map their locations using different frequencies.

But of the five jaguars that we end up spotting over the course of two days (with names like Timbo, Aroeira, Hades and Flor), only one of them has been collared to provide Onçafari with its coordinates. The other sightings are merely a testament to how well the jaguar habituation program is working.

(function(d,u,ac){var s=d.createElement(‘script’);s.type=’text/javascript’;s.src=’https://a.omappapi.com/app/js/api.min.js’;s.async=true;s.dataset.user=u;s.dataset.campaign=ac;d.getElementsByTagName(‘head’)[0].appendChild(s);})(document,123366,’t5vozbt52e4hnenmh9mb’);

According to Onçafari, only 16% of guests at the Caiman Ecological Refuge reported seeing jaguars in 2013. Ten years later, the percentage was 100. Although Onçafari never guarantees a sighting, the likelihood of spotting a jaguar (or jaguars) here really is possibly the best on the planet.

After about 40 minutes in Aracy’s presence, it’s time to move on. But before starting up our 4×4 vehicle’s engine, Morgado clears his throat. It’s a way to indicate to the felines that there’s a louder sound coming and remind these big cats that they can keep on keeping on without feeling threatened.

Natural Habitat Adventures’ Jaguars & Wildlife of Brazil’s Pantanal includes a few nights lodging at the Caiman Ecological Refuge and time spent with the Onçafari Jaguar Project, as well as one of the reserve’s spectacular Pantaneiro cowboy dinners—complete with an array of spit-roasted meat.

Participants also have an opportunity to spot jaguars in the northern Pantanal and see other species like toucans, howler monkeys, giant armadillos and big-headed swamp turtles.

Want to make your experience even more amazing? Tack on a trip extension to see one of the world’s mightiest waterfalls, the more-than-a-mile-long Iguazu Falls, which straddles the border between Brazil and Argentina.

The post Tracking Jaguars with the Onçafari Project: Conservation Travel in Brazil’s Pantanal first appeared on Good Nature Travel Blog.

It was in the early morning when we first spotted Aracy, positioned near a small waterhole in Brazil’s southern Pantanal region. We followed her through the grasslands, watching the jaguar meander among trees and along the occasional dirt pathway—at one point, even walking within several feet of our open-sided 4×4 vehicle—until she spotted a herd of capybaras grazing beside a lake. “Keep quiet,” our guide Lucas whispered. “She’s about to make her move.”

In an instant, the capybaras were running into the water with Aracy sprinting behind them, hoping for an early day feast. Although luck wasn’t on her side this round, the enormous feline put on a show for the ages.

Wildlife is a given in Brazil’s massive Pantanal, a more than 75,000 square-mile UNESCO Biosphere Reserve that’s home to the largest tropical wetlands and flooded grasslands on the planet. Everything from squadrons of peccaries (hoofed mammals that resemble pigs) to alligator-like caiman call this incredible natural region—one that stretches across portions of Brazil, Bolivia and Paraguay, covering an area that’s equivalent to the size of Belgium, Holland, Portugal and Switzerland combined—home.

In fact, the Pantanal hosts South America’s densest concentration of wildlife: we’re talking animals as varied as giant anteaters, musk deer, tapir and blue-and-yellow colored hyacinth macaws. Impressive, since many visitors flock to the continent’s other fauna-filled destinations, like the Amazon rainforest, without knowing that these wetlands exist.

(function(d,u,ac){var s=d.createElement(‘script’);s.type=’text/javascript’;s.src=’https://a.omappapi.com/app/js/api.min.js’;s.async=true;s.dataset.user=u;s.dataset.campaign=ac;d.getElementsByTagName(‘head’)[0].appendChild(s);})(document,123366,’pqjonhkt1vutpsrffqge’);

These days, however, the Pantanal is gaining traction among wildlife lovers, thanks in large part to the efforts of Onçafari, a project established to promote conservation through ecotourism, mainly habituating jaguars to safari vehicles with the notion that the more people see these stealth cats in the wild, the more they’ll likely do something to save them.

> Learn about World Wildlife Fund’s conservation initiatives in Brazil’s Pantanal

© Cassiano “Zapa” Zaniboni

Former Formula 1 racing driver Mario Haberfeld established Onçafari in August 2011. Its name is a combination of “onça,” the Portuguese word for “jaguar,” and “safari,” which means “journey” in Swahili. Haberfeld was inspired to start the project after visiting Africa, where wildlife such as lions, elephants, and hyenas have grown up around safari vehicles.

The Brazil native wanted to bring the same type of ecotourism to the Pantanal, helping to preserve its biodiversity in the process. Although the organization also works with other species ranging from giant otters to crab-eating foxes, in the Pantanal, it’s the jaguars that draw the most attention.

Jaguars are similar to leopards, their African counterparts, though they’re stockier than leopards and more muscular. Each one is also highly unique. Some are more golden in color, their whiskers longer or shorter, and their faces narrower or fuller.

Historically, their range stretches from Argentina north up to Arizona’s Grand Canyon, though their population has decreased by 25% in just over two decades, spurred in large part by deforestation and illegal logging. Today, jaguars occupy less than half of where they once roamed, with sightings only as far north as Mexico’s Sonora state and occasionally crossing the border into Arizona. Seeing one in the wild has long been a remarkably rare experience.

Lucas Morgado is an Onçafari biologist who is well-versed in tracking wildlife. He’s also our safari guide in Brazil’s southern Pantanal. He tells us the story behind Aracy. How she was born back in 2020 and has been in the proximity of vehicles all of her life. She’s the daughter of Isa, one of the first two jaguars to be reintroduced by Onçafari to the Pantanal after losing her mother at a young age. And that she’s missing the tip of her left ear.

©Helder Brandao de Oliveira

We also learn about jaguars in general: things like their having the strongest bite of all cats—even lions and tigers—and how the rosette patterns on their fur are as unique as human fingerprints. And while they’re typically solitary creatures, these elusive cats sometimes form coalitions to survive. Much like us?

Of the estimated 15,000 to 64,000 jaguars remaining in the wild, more than half of them live within the Amazon Rainforest and the Pantanal. About 60 to 80 of these reside inside the 204-square-mile Caiman Ecological Refuge, a renowned private reserve that happens to be the site of our spacious lodge.

Caiman Ecological Refuge is also the site of the Onçafari jaguar team’s scientific research center. Here, the project’s team members constantly evaluate the felines’ health and monitor their behavior through motion sensor cameras, direct observation, and a handful of GPS-equipped radio collars that can map their locations using different frequencies.

But of the five jaguars that we end up spotting over the course of two days (with names like Timbo, Aroeira, Hades and Flor), only one of them has been collared to provide Onçafari with its coordinates. The other sightings are merely a testament to how well the jaguar habituation program is working.

(function(d,u,ac){var s=d.createElement(‘script’);s.type=’text/javascript’;s.src=’https://a.omappapi.com/app/js/api.min.js’;s.async=true;s.dataset.user=u;s.dataset.campaign=ac;d.getElementsByTagName(‘head’)[0].appendChild(s);})(document,123366,’t5vozbt52e4hnenmh9mb’);

According to Onçafari, only 16% of guests at the Caiman Ecological Refuge reported seeing jaguars in 2013. Ten years later, the percentage was 100. Although Onçafari never guarantees a sighting, the likelihood of spotting a jaguar (or jaguars) here really is possibly the best on the planet.

After about 40 minutes in Aracy’s presence, it’s time to move on. But before starting up our 4×4 vehicle’s engine, Morgado clears his throat. It’s a way to indicate to the felines that there’s a louder sound coming and remind these big cats that they can keep on keeping on without feeling threatened.

Natural Habitat Adventures’ Jaguars & Wildlife of Brazil’s Pantanal includes a few nights lodging at the Caiman Ecological Refuge and time spent with the Onçafari Jaguar Project, as well as one of the reserve’s spectacular Pantaneiro cowboy dinners—complete with an array of spit-roasted meat.

Participants also have an opportunity to spot jaguars in the northern Pantanal and see other species like toucans, howler monkeys, giant armadillos and big-headed swamp turtles.

Want to make your experience even more amazing? Tack on a trip extension to see one of the world’s mightiest waterfalls, the more-than-a-mile-long Iguazu Falls, which straddles the border between Brazil and Argentina.

The post Tracking Jaguars with the Onçafari Project: Conservation Travel in Brazil’s Pantanal first appeared on Good Nature Travel Blog.