Down-filled bedding doesn’t belong in a landfill, especially when there are many better options for…

The post How To Reuse or Recycle a Down Comforter (and Why You Should) appeared first on Earth911.

Down-filled bedding doesn’t belong in a landfill, especially when there are many better options for…

The post How To Reuse or Recycle a Down Comforter (and Why You Should) appeared first on Earth911.

When touched, the hypersensitive makahiya plant folds its minuscule leaflets inward, protecting itself from any potential threat.

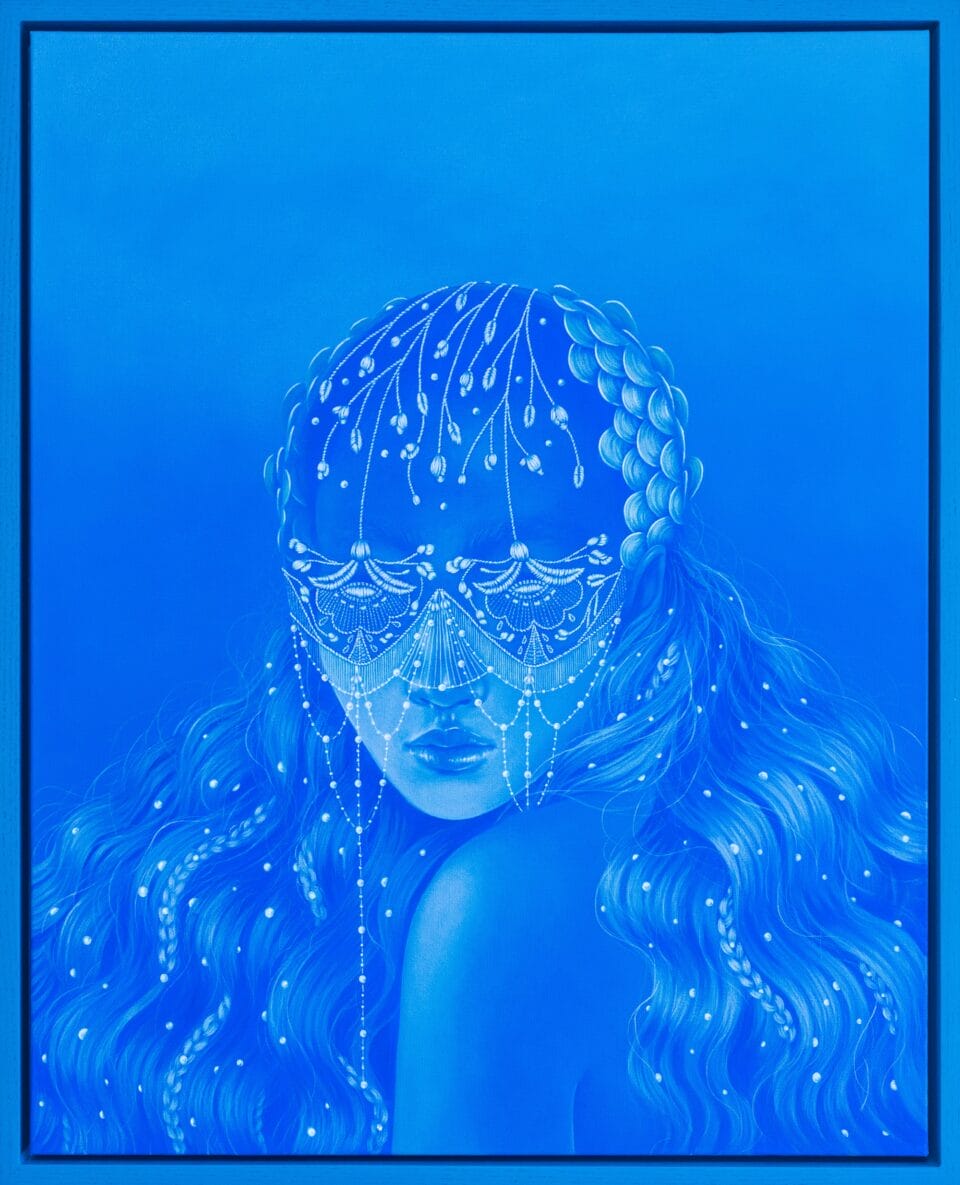

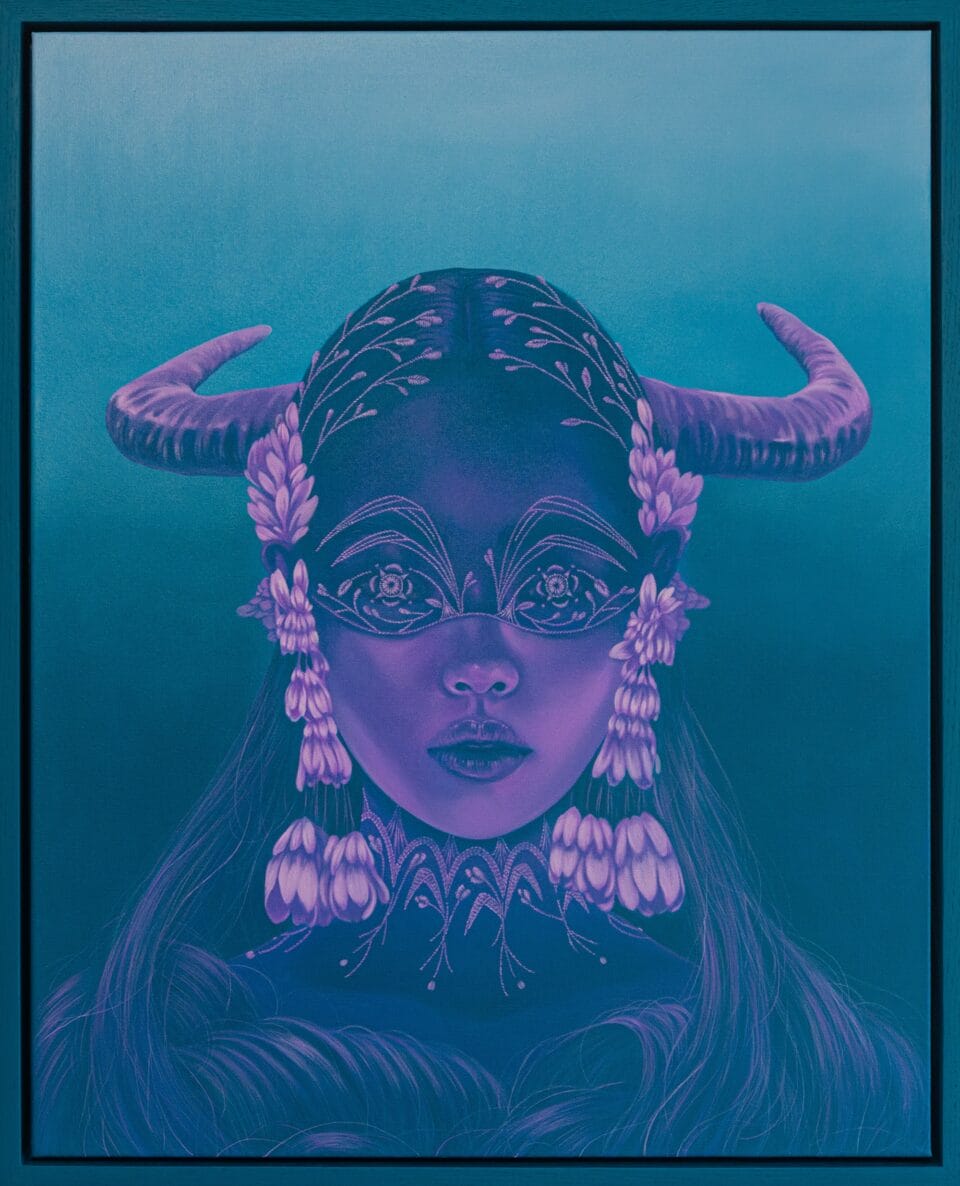

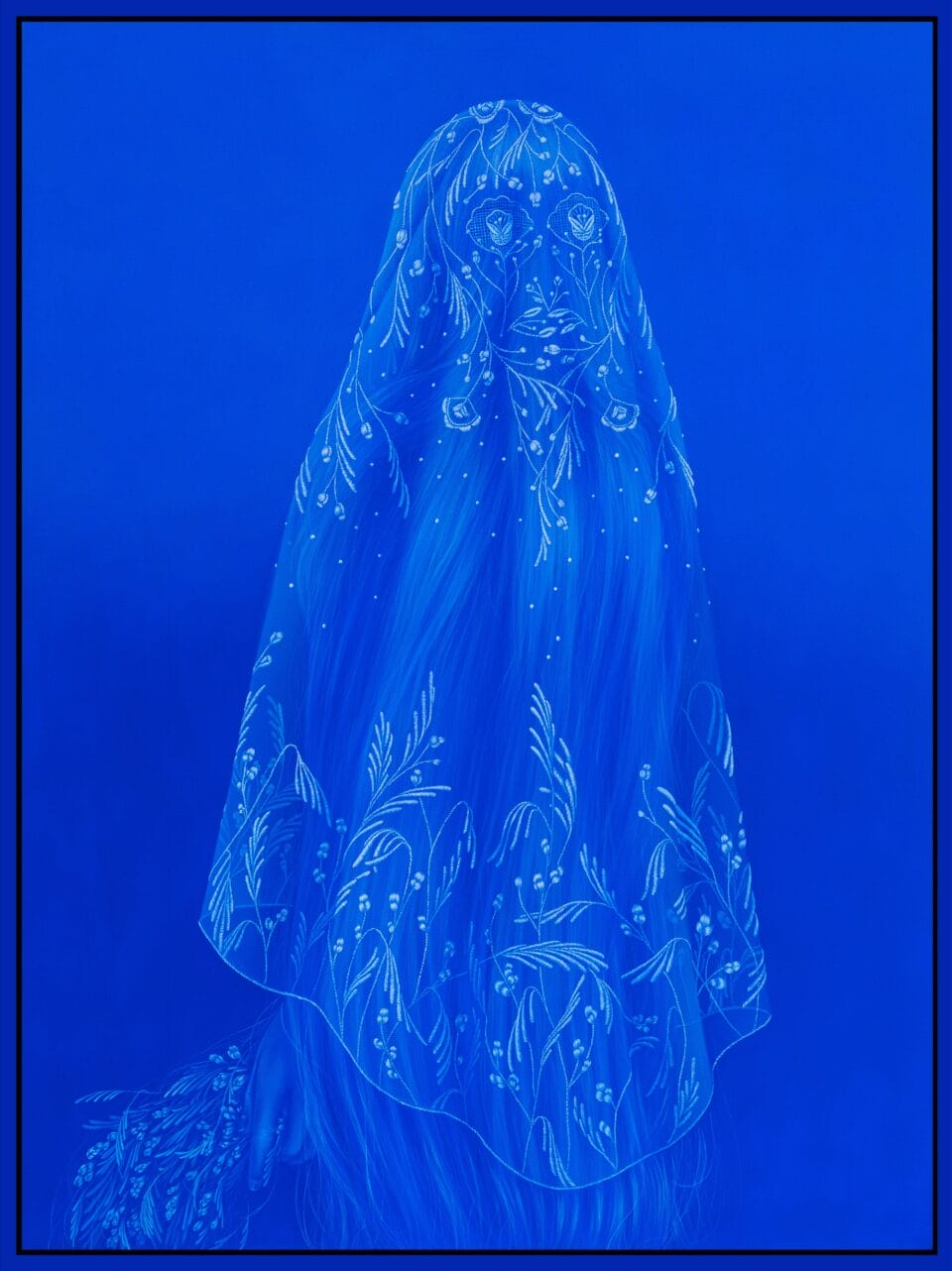

Florence Solis draws on this defensive response in an ethereal collection of portraits. Beginning with digital collages that meld figures and delicate, organic ornaments, the Filipino-Canadian artist translates the imagined forms to the canvas. Shrouded in dainty, beaded veils or entwined with botanicals, each protagonist appears bound and concealed, their bodies and faces obscured by hair or grass.

As Solis sees it, the figures may be restricted, but they’re also able to find strength and transformation. “Filipino women, much like the makahiya, have been taught to yield, to soften, to take up less space,” she says. “And yet, beneath this quietness lies an undeniable force—one that persists, adapts, and reclaims space in its own way.”

Working in saturated, often single-color palettes, Solis renders figures who appear to harness magical powers. She references Filipino folklore and the belief in the power of the everyday to lead to the divine, painting women rooted in tradition and myth, yet determined to see their transformation through.

The vivid portraits shown here will be on view at EXPO CHICAGO this week with The Mission Projects. Find more from Solis on Instagram.

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $7 per month. The article In Luminous Portraits, Florence Solis Invokes Feminine Power Amid Constraint appeared first on Colossal.

Four exceptional educators earned a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to witness the monarch migration on Nat Hab’s Kingdom of the Monarchs adventure, journeying deep into Central Mexico’s forested highlands alongside expert naturalist guides. Surrounded by towering oyamel fir trees blanketed with millions of delicate, orange-and-black butterflies, the teachers observed firsthand the extraordinary spectacle of monarchs gathering at their winter roosting grounds. Here, two of our Monarch Butterfly Scholarship Grant recipients share reflections on this unforgettable experience:

This winter, I had the incredible honor of receiving the Monarch Butterfly Grant Scholarship from Natural Habitat Adventures, which provided a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to visit the monarch butterflies in their overwintering sanctuaries in Mexico—something I’ve taught my first-grade students about for years but never dreamed I’d witness firsthand.

Getting to Mexico was challenging due to a winter storm in my area. Thankfully, I made it through the snow to the airport, and my flight miraculously departed on time. It truly felt like the trip was meant to be.

Upon arriving in Mexico City, I met fellow scholarship-winning educators. Together, we visited an anthropology museum filled with fascinating artifacts from ancient Maya, Inca and Aztec civilizations—perfectly aligned with an upcoming unit for my first graders. I eagerly took numerous pictures, excited to bring these real-world visuals back to my classroom.

The following day, we journeyed into the mountains to visit one of the monarch sanctuaries. The experience was surreal—traveling in open-bed trucks, riding horseback and hiking the mountain trail. Coming from small-town Indiana, I never imagined myself in such a remote, sacred and beautiful location. Reaching the grove where thousands of monarchs roosted overwhelmed me emotionally. The trees were heavy with butterflies, their delicate wings creating an ethereal hush. It was cold and damp, so most monarchs remained stationary, but just standing there—witnessing something I’d only read about—was breathtaking.

(function(d,u,ac){var s=d.createElement(‘script’);s.type=’text/javascript’;s.src=’https://a.omappapi.com/app/js/api.min.js’;s.async=true;s.dataset.user=u;s.dataset.campaign=ac;d.getElementsByTagName(‘head’)[0].appendChild(s);})(document,123366,’btgjafa81bwlejf6pzef’);

Each subsequent sanctuary visit was uniquely special, and we learned so much from our local guides and each other. I eagerly shared my journey in real-time with my students, sending emails and videos directly from the mountain, and prepared a travel journal for my class to follow my journey. This experience represented everything education should be: authentic, meaningful and full of wonder.

This incredible journey enriched my life and provided powerful stories to share with my students. Standing where the monarchs rest is an experience I’ll carry forever.

The ride up to the Monarch Sanctuary was thrilling and refreshingly cool in the back of our truck. I was excited to ride on horseback, something I hadn’t done since I was a teenager. After dismounting and beginning the hike up the mountain right behind our guide, reality truly set in—I was finally going to witness the phenomenon of overwintering monarchs. After years of teaching children and adults about monarch life cycles, the migration and milkweed, and spending autumns tagging monarchs for citizen science, it felt surreal to be there in person. Breathing heavily from the climb and feeling the burn in my legs, I paused when our guide pointed into the trees. The day was foggy, and through the mist, I could just make out the monarch clusters gathered in the branches. Standing quietly, I was awed by the sight before I started capturing photos and videos to bring this incredible experience back home. I even activated my Project Monarch app, hoping to detect a monarch equipped with a transmitter.

It was surreal to stand silently among the trees, observing hundreds of monarchs clustered together, appearing as though they were dripping from the branches. I kept thinking, “I’m really here.” The variety in the formations fascinated me—some clusters thick and dense, others spread across branches. Monarchs also scattered the ground and bushes, with the occasional solitary butterfly resting alone.

Our Nat Hab Expedition Leaders anticipated every possible need, blending adventure with comfort. They shared extensive knowledge about monarchs, local culture and history, always ready to answer questions and accommodate special requests like birdwatching and tasting local chocolate.

This scholarship provided invaluable experiences, photographs and knowledge I can now share with my students and community through presentations, walks and tagging events, encouraging others to care about monarchs and their habitats. Thank you for this amazing opportunity!

The post Among the Butterflies: Reflections from Our Monarch Scholarship Winners first appeared on Good Nature Travel Blog.

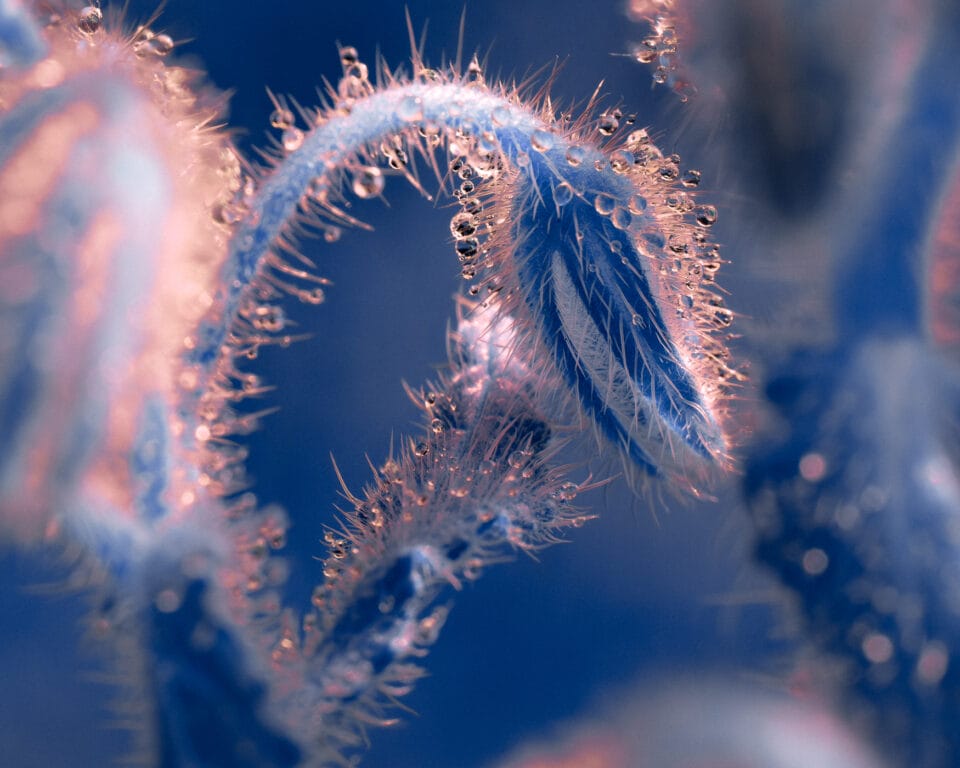

Tom Leighton (previously) is known for highlighting plants’ photosynthesis process by swapping their characteristic greens for otherworldly fluorescent colors. Often focused on the nightlife of specimens found around his Cornwall home, Leighton photographs in a manner that turns common species into extraordinary subjects.

His newest series, Spines, expands on this trajectory. The macro images concentrate on the fine fibers cloaking stems and flowers. Water droplets cling to the surfaces as if the plants had just emerged from a heavy downpour. The glistening botanicals capture the surrounding light, while the thick dew drops add a glimmering, skewed view of the lifeforms that reside underneath.

Prints of Leighton’s images are available on his website. Keep up with his latest projects on Behance and Instagram.

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $7 per month. The article Water Droplets Cling to Fluorescent Plant Spines in Tom Leighton’s Alluring Photos appeared first on Colossal.

Picture an expanse of wetlands so vast it’s five times larger than the Florida Everglades—an enormous freshwater floodplain pulsing with a near-constant cycle of inundation and retreat. This dynamic landscape is the Pantanal, home to some of South America’s largest and most charismatic species: giant otters, giant armadillos, giant anteaters, hyacinth macaws and the heaviest cat in the Americas—the jaguar. It is a haven of biodiversity and beauty, a vital artery of water and life.

Recently, we had the pleasure of speaking with Abby Martin, founder of the Jaguar Identification Project, about her team’s efforts to better understand and protect Brazil’s biggest cat. Over the years, this project has grown from a personal passion into a conservation tool embraced by the local community and by travelers who yearn to see these magnificent creatures thriving in their natural habitat.

To fully appreciate the role of the Jaguar Identification Project, it helps to understand the Pantanal itself. Covering 42 million acres, this mosaic of swamps, forests, rivers and floodplains is renowned for holding the highest density of jaguars on Earth.

Yet the Pantanal isn’t just about big cats—it’s also a watery crucible of life that supports more than 650 bird species, alongside tapirs, capybaras, caimans and countless amphibians, reptiles and insects. Giant river otters—playful and social carnivores—cruise through channels hunting fish, while families of capybaras forage along the shores. Herds of grazing animals and an orchestra of bird calls color the soundscape at dawn. All of these creatures depend on the Pantanal’s seasonal flood pulse, a rhythmic rise and fall of water levels that triggers migrations, fruiting cycles and breeding seasons.

But that natural cycle is weakening. Increased deforestation in the surrounding Cerrado savanna and the Amazon Rainforest—ecosystems that feed moisture into the Pantanal’s waterways—has altered the timing and intensity of rains. As rainfall patterns become erratic, droughts intensify. These changes have led to larger, more frequent wildfires, devastating huge areas of this once-lush terrain. In some recent years, catastrophic fires have burned as much as 40% of the biome, dealing a severe blow to the Pantanal’s flora and fauna. Abby notes that fires—once part of the region’s natural rhythm—have grown so intense and frequent that recovery between burn cycles becomes more challenging. The Pantanal’s watery heart is under unprecedented strain.

(function(d,u,ac){var s=d.createElement(‘script’);s.type=’text/javascript’;s.src=’https://a.omappapi.com/app/js/api.min.js’;s.async=true;s.dataset.user=u;s.dataset.campaign=ac;d.getElementsByTagName(‘head’)[0].appendChild(s);})(document,123366,’pqjonhkt1vutpsrffqge’);

The Pantanal has long been known as the world’s premier place to view wild jaguars. One reason is the region’s abundance of prey and its relatively open habitats. Each dry season, water recedes from the floodplains, concentrating wildlife along permanent rivers. Jaguars follow, drawn by the promise of easily accessible prey—such as capybaras and caimans—that congregate at the water’s edge. Over time, some jaguars in this area have grown surprisingly tolerant of human presence. This habituation means that visitors can often observe wild jaguars from boats at a respectful distance. It’s a remarkable wildlife experience, one of the few places on Earth where sightings of the Americas’ largest cat are almost guaranteed during the dry season.

Despite this, jaguars remain under threat. Across their range, the biggest risks they face are retaliatory killings by ranchers, habitat loss, and the escalating toll of climate-related pressures such as drought and fire. Estimates suggest 200–300 jaguars may be killed annually in the Pantanal due to rancher conflicts, significantly impacting local populations. Jaguars are also feeling the effects of relentless habitat conversion on the fringes of their wetland home—land cleared or burned for agriculture, cattle grazing and monocultures. The Pantanal’s delicate water system depends on surrounding ecosystems to maintain the floods and seasonal moisture that nurture biodiversity. When these outer ecosystems are stripped away, the Pantanal suffers—and so do the jaguars.

Abby Martin’s path to the Pantanal began as many great adventures do: with a single transformative trip. She first traveled to Brazil as a university student in a climate change course. After experiencing the Pantanal’s vibrant landscape and wildlife, Abby was hooked. She soon found her way back, this time as a volunteer jaguar researcher, and her involvement deepened.

In 2013, the Jaguar Identification Project (JIP) was born. Its aim was simple yet ambitious: monitor and identify individual jaguars along the rivers of the northern Pantanal by using their unique spot patterns. Each jaguar’s rosettes—those distinctive clusters of spots—are like fingerprints, allowing scientists and citizen scientists alike to distinguish one cat from another. Early on, Abby saw the potential for citizen science. If travelers and guides could learn to identify jaguars and report sightings, then the project could gather data beyond what any single research team could manage alone.

Initially, Abby faced a steep learning curve. Funding was scarce. She worked as a guide, driving boats of tourists along these jaguar-rich waterways, simultaneously collecting data, snapping photos and encouraging travelers to share their images. Over the years, JIP compiled a growing catalog of hundreds of jaguars, charting births, deaths, arrivals and departures. By 2016, the team published their first Jaguar ID book and began distributing it to lodges and local communities. Soon, visitors were flipping through pages, exclaiming, “I saw Madroza!”—a well-known female jaguar famed for her dramatic river-edge hunting skills, leaping down from logs to ambush caimans below.

Join expert naturalist guides on our trip Jaguars & Wildlife of Brazil’s Pantanal to discover South America’s largest wildlife sanctuary—the best place on the planet to spot jaguars in the wild! © Helder Brandão de Oliveira

JIP’s success hinges on the synergy between research and ecotourism. Every visitor armed with a camera is a potential data collector. When tourists share their photos, they contribute vital snapshots of jaguars that JIP staff might not see themselves. A cat thought to have vanished for years might turn up, revealing she’s still alive and raising cubs. A once-unknown individual can be identified and named.

This flood of citizen data allows researchers to assess changes in jaguar demographics and behavior over time. After the mega-fires of 2020 and subsequent years, Abby’s team detected a fascinating—and initially puzzling—trend. The number of jaguars identified along the rivers soared. At first glance, one might interpret this as a post-fire recovery or even a boon for jaguars. But a closer look reveals a different story.

The fires destroyed vast swaths of the Pantanal’s interior habitat. Jaguars, unable to find suitable shelter and prey in the scorched landscapes, moved toward the rivers—safe havens where water and life persisted. So the population spike at the rivers wasn’t a sign of overall recovery; it was a gathering of refugees seeking the last green corridors of habitat. Long-term data like this, made possible by citizen contributions, help scientists understand how jaguars respond to environmental changes, informing future conservation measures.

With abundant data, JIP has uncovered remarkable jaguar behavior. They’ve documented coalitions of male jaguars—unrelated or distantly related individuals that team up for a competitive edge. They’ve also recorded the first confirmed case of jaguar infanticide, a behavior previously known in other big cats but never before confirmed for jaguars in the wild. These behavioral insights are not only fascinating; they also help predict how jaguars might adapt to climate pressures, shifts in prey availability and changes in habitat quality.

This is research that can have global implications. As climate change intensifies and extreme weather events become more common, understanding how top predators like jaguars respond can guide conservation strategies worldwide. Jaguars serve as umbrella species; safeguarding them helps protect countless other species and the entire ecosystem.

While tourism provides critical benefits such as funding research and deterring poaching, it must be carefully managed to protect wildlife. Too many boats pursuing limited jaguar sightings can stress the animals and disrupt their hunts, causing them to retreat into dense vegetation. Without proper guidelines and enforcement, excessive tourism pressure can negatively affect both wildlife welfare and the quality of visitor experiences. Conservation travel, however, prioritizes sustainable practices and wildlife protection. In Brazil’s Pantanal, responsible tourism supports the preservation of extraordinary biodiversity, from jaguars and giant otters to vibrant birdlife. It also empowers local communities through sustainable economic opportunities, incentivizes habitat protection, and funds critical scientific research and environmental education. By traveling with Natural Habitat Adventures, guests participate in immersive, expertly guided experiences that place wildlife-friendly practices and meaningful community engagement at their core, directly contributing to the Pantanal’s long-term conservation.

The Jaguar Identification Project has also become a vehicle for community engagement. Abby and her colleagues have brought local guides, some of whom were once hunters or fishermen, into the fold. These community members now help set up and maintain camera traps deep in the park’s interior—work that’s physically demanding and logistically challenging. Their intimate knowledge of the landscape and its wildlife is invaluable, and their participation ensures that conservation efforts benefit those who live and work in the region.

For the future, Abby dreams of securing more resources, including the possibility of purchasing private lands to act as buffer zones and wildlife corridors. By protecting riverine forests that serve as vital ecological refuges, she hopes to preserve what makes the Pantanal so special—a place where jaguars still roam free and flourishing.

JIP’s work shows how a single traveler’s photo or a small donation can contribute to a larger conservation mission. If you’re fortunate enough to visit the Pantanal, consider connecting with the project. Buy a Jaguar Field Guide, share your images and educate yourself about the importance of these forests and wetlands. Even from home, there are ways to help:

Sitting in a boat at the meeting of the waters—where rivers converge amid lush gallery forests—one feels the pulse of the Pantanal’s “freshwater heart.” The jaguars that grace these shores have thrived here for millennia, each generation adapting to the changing flood cycles and shifting landscapes. In recent years, that world has been thrown off balance. Yet, as Abby Martin’s work and the dedication of countless citizen scientists show, it’s not too late to help.

The Jaguar Identification Project reminds us that knowledge is power. Each identification, each data point and each traveler’s shared photo deepens our understanding of jaguar life. Armed with that knowledge, we can push for stronger protections, more thoughtful tourism guidelines and better land-use policies. By working together—conservationists, travelers, local communities and the global public—we can ensure that the Pantanal’s jaguars continue to reign in their rightful place, inspiring wonder for generations to come.

The post The Jaguar ID Project: A New Chapter in Protecting Brazil’s Biggest Cat first appeared on Good Nature Travel Blog.

“I want to explode the idea of beautiful ikebana,” says Kosen Ohtsubo, one of the foremost conceptual artists working in the Japanese tradition.

Since the 1970s, Ohtsubo has been unsettling the ancient art of flower arranging. Incorporating atypical botanicals like cabbage leaves or weaving in unconventional materials like bathtubs and scrap metal, the artist approaches making with the mindset of a jazz musician, a genre he frequently listens to while working. Improvisation and experimentation are at the core, along with an unquenchable desire for the unexpected.

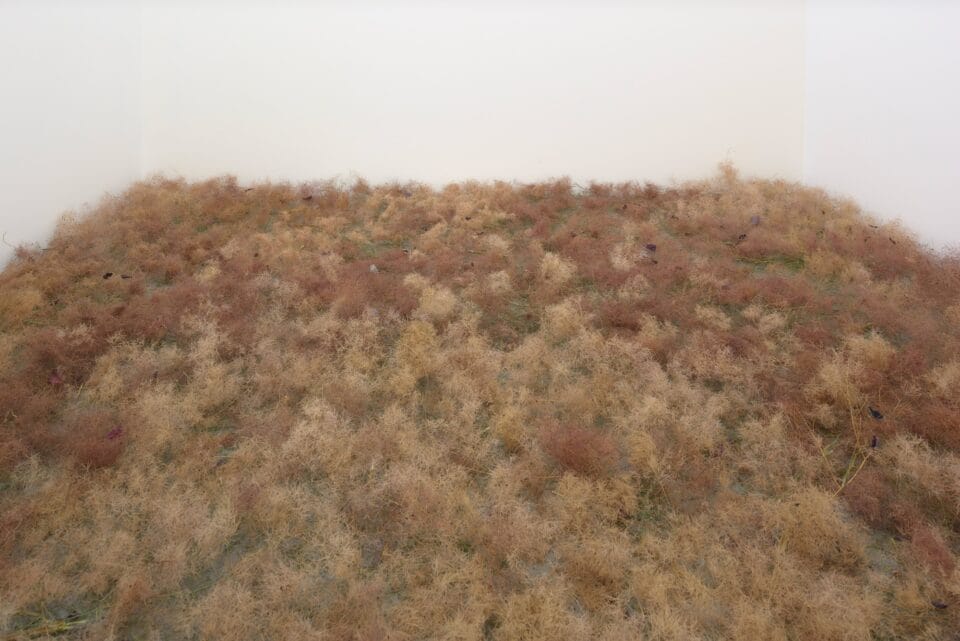

An exhibition at Kunstverein München in Munich pairs Ohtsubo with Christian Kōun Alborz Oldham who, after discovering the ikebana icon’s work in a book in 2013, became his student. Titled Flower Planet—which references a sign that hangs outside Ohtsubo’s Tokorozawa home and studio—the show presents various sculptures and installations that invite viewers to consider fragility, decay, and the elusive qualities of beauty and control.

Given the ephemeral nature of the materials, photography plays an important role in most ikebana practices as it preserves an arrangement long after it has wilted. This exhibition, therefore, pairs images of earlier works with new commissions, including Ohtsubo’s standout orb titled “Linga München.” Nested in a bed of soil and leaves, the large-scale sculpture wraps willow with metal structures and positions a small candle within its center.

Similarly immersive is “Willow Rain,” which suspends thin branches from the ceiling. Subverting the way we typically encounter fields of growth, the work is one of many in the exhibition that seeds questions about our relationship to the natural world and the limits of human control.

Flower Planet is on view through April 21. Explore Ohstubo’s vast archive on Instagram.

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $7 per month. The article An Ikebana Artist and His Student Sow an Unconventional Approach to Flower Arranging appeared first on Colossal.

Driving across the plains of the Serengeti, every sense becomes sharpened: eyes alert as you scan the horizon, inhaling the mingling scents of lemon bush and wild mint, you listen to the echos of animals calling in the distance, just as Africa has called to you. It’s incomprehensibly special, this land shaped by vast and varied episodes of geology, ecology and history. Our origins are found in Tanzania’s gorges and valleys, the unearthed fossilized bones of our ancestors dating back millions of years. Spanning as long as human existence, we have lived side by side with the other creatures of this planet. It is human nature to want to know where we came from; to seek out the mysteries of our past. We have always sought out a sense of belonging, and perhaps part of what we are searching for is here, in a landscape that can never truly belong to anyone but nevertheless leaves us linked, imprinting on our soul.

As the sun falls, burning red, we quietly approach a black rhinoceros, affectionately known as Mama Julie. She moves slightly, and a tiny calf becomes visible, mere weeks old. Its curled-up form is in stark contrast with the powerful, looming figure of the rhino mother before us—this is nature at her strongest and most vulnerable. It’s a striking end to a safari filled with wildlife spectacles: a cheetah with two cubs feasting on a gazelle, outlined by purple streaks of lightning as the sky unleashes a torrent of rain; a wildebeest struggling against a crocodile in the raging waters of the Mara River; a leopard asleep in a tree, her spotted pelt golden in the dappled sunlight—she lifts her head, piercing green eyes fixed on me. Reflecting on all I have paid witness to, I sit by the fire under a kaleidoscope of stars, caressed by wind and smoke, talking until the coals burn low and become nothing more than glowing embers. Lions call in the distance. I understand what our guide means when he says the Serengeti feels like home.

We leave the following morning, still in a daze at the number of rare species and unique interactions we have encountered. I stare out at the open plains, so expansive I can just make out the curvature of the Earth. Navigating dusty roads, we pass a lioness sunning herself on a termite mound, a recent kill beside her, as zebra graze on viridescent grasses that have sprung forth since the recent rains. Yellow-billed storks snatch fish from a glittering pool as baboons wade in to feed on fragrant water lilies. Over the past two weeks, we have become so accustomed to watching life unfold in the most enthralling and heartwrenching ways.

Beauty among the thorns: a parallel replicated time and again in the savanna, and in our own lives.

We come upon the huddled form of a baby elephant seeking shelter, entirely alone on the endless plains. He flaps his ears, disproportionately large on his small body. His mother is gone. She has died, either of natural causes or poaching, our guide observes. He radios the rangers and tells us this calf is a suitable candidate for a rescue and rehabilitation center like the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust. Three months before, I had adopted an orphaned elephant, Emoli, from the very same trust in my grandmother’s name. She loves reading updates on the little one’s progress, as he is bottle-fed milk and nestled under Maasai blankets each night, cocooned in warmth. Many elephants have been saved and reintegrated into the wild through the refuge’s inspiring work. Still, during times of drought or spikes in poaching, the number of animals in need grows overwhelming. The gravity of the elephants’ plights is made clear in the graveness of our Expedition Leader’s words: “We can’t afford to lose another one.”

Memories of the Serengeti do not leave you; they live within you, ingrained into your very being. The last pictures I am left with are of the elephant calf, along with the young rhino and cheetah cubs. The future of the Serengeti depends on their survival. The wild animals found here are like no other, and their ecosystem, one of astonishing beauty and inevitable harshness, hangs in a delicate balance. Humans have played their part in throwing that balance off-kilter. But conservation travel has such power; power to change and inspire. The effect of such a place on one’s outlook can be life-altering, leaving us with a desire to preserve and cherish what we were once removed and disconnected from. We begin the process of remembering, retracing our past and laying the groundwork to protect and restore our planet’s future. If we can once again recognize ourselves as a part of the natural world rather than removed from it, then maybe we stand a chance at ensuring the wildlife of the Serengeti lives on forevermore.

All Photos © Emily Goodheart

(function(d,u,ac){var s=d.createElement(‘script’);s.type=’text/javascript’;s.src=’https://a.omappapi.com/app/js/api.min.js’;s.async=true;s.dataset.user=u;s.dataset.campaign=ac;d.getElementsByTagName(‘head’)[0].appendChild(s);})(document,123366,’tzdleqisjlsvwy8cchs5′);

The post Serengeti Calling first appeared on Good Nature Travel Blog.

History and geography teachers often point out the silliness of Greenland’s name. The Arctic country is covered with a barren ice sheet spanning 660,000 square miles, or roughly 80% of the country’s surface. There’s not exactly much green to be found!

According to the Icelandic Sagas, Eric the Red, who had been exiled from Iceland for murder, came to Greenland’s glacial shores in the late 10th century and dubbed the place “Grœnland” in the hopes of attracting settlers to the remote outpost with the false promise of abundant forests and fields.

He may have been just a little ahead of his time. Research shows that in the not-too-distant future, climate change could melt the edges of Greenland’s ice sheet, opening up fertile soil for new seeds and plants to take hold. But would a greener Greenland be good for the country—or the planet?

(function(d,u,ac){var s=d.createElement(‘script’);s.type=’text/javascript’;s.src=’https://a.omappapi.com/app/js/api.min.js’;s.async=true;s.dataset.user=u;s.dataset.campaign=ac;d.getElementsByTagName(‘head’)[0].appendChild(s);})(document,123366,’lgdlnrsnwsc77fyklkpb’);

The Greenland ice sheet is losing an average of around 250 billion metric tons of ice per year—and these losses have shown to be speeding up over time. The ice contains enough water to raise global sea levels by 24 feet if all of it melted. The year 2021 marked the 25th year in a row in which the ice sheet lost more mass during the melting season than it gained during the winter.

Warm air temperatures cause melting to occur on the surface of the ice sheet, a process that is responsible for around half the ice Greenland loses each year. The other half comes from glaciers at the ice sheet’s edge crumbling into the sea. When that happens, it churns up the waters—and that turbulence helps heat rise up from deeper parts of the ocean, warming the waters coming into contact with the ice and melting the glaciers even faster.

As a result, Greenland, researchers predict, could soon begin to look a little bit like Alaska or western Canada, though the exact composition of trees and bushes depends upon which species take advantage of the new ecological niches that form when ice uncovers soil.

© Colby Brokvist

Greenland is special in so many ways when it comes to ecological conservation. Although it is the 12th-largest country in the world (it’s approximately the size of Western Europe or the main part of the U.S.), Greenland has the lowest population density of any country on the planet. Only 56,000 people call Greenland home; if they were all to spread out, each Greenlander would have about 25 square miles to themselves.

The entire northeast of Greenland is one massive national park that was established in 1974. It’s the largest national park in the world and a sanctuary for Arctic wildlife such as the Arctic fox, collared lemming, Arctic hare and gray wolves.

With so few people and even fewer cars and industry (the longest road for vehicles in the country is only around 20 miles long), Greenland also has some of the purest air in the world. You can drink freely from any of the streams or rivers in the country—no filter required.

Greenland is already greener than most visitors on our East Greenland Arctic Adventure expect. Colorful flowers, lush meadows and hardy plants spring up when the snow starts to melt and the summer’s mild winds blow. Our Expedition Leaders even guide our guests into a place called the Valley of Flowers, where beautiful lakes are ringed with wildflowers.

> Read: What Climate Change Will Mean for Greenland’s Arctic Wildflowers

The vegetation is richest and most diverse in the southwest, which, compared to the rest of the country, has a relatively mild climate with wooded areas in the protected inner fjords. Elsewhere in Greenland, there are tundras with grasses and sedges, carpets of moss, mushrooms, flowering plants like bog rosemary and yellow poppy, and blueberry and crowberry bushes.

In 1911, researchers reported that Greenland was home to 310 species of vascular plants, including 15 endemic species. Today that number has jumped up to nearly 500 species and rising. Practically all of Greenland’s native vegetation disappeared during the ice age; the existing plant life came mostly from North America.

How’s that? Well, a study conducted in Svalbard, an archipelago north of Norway with a similar ecosystem as Greenland, found 1,019 seeds of 53 species clinging to just 259 travelers’ shoes upon arrival. Twenty-six of those species germinated in Arctic conditions when given the opportunity. Migratory birds coming from North America have also been found to deposit seeds that had been stuck to their plumage and feet or passed through their bowels.

Currently, only five species of trees or large shrubs occur naturally in Greenland: Greenland mountain ash, mountain alder, downy birch, grayleaf willow, and common juniper. Even these currently grow only in scattered plots in the far south.

However, field experiments have confirmed that a range of other species, including Siberian larch, white spruce, lodgepole pine and Eastern balsam poplar, could establish in Greenland if given the chance. Those species, along with the five long-established native varieties, may begin to spread as temperatures warm with climate change.

Researchers built a computer model of Greenland’s predicted climate for the next 100 years, onto which they overlaid with known data for various North American and European tree species’ ideal habitat niches. Within a century, they found, all 56 species of trees and shrubs they tested would likely be ideally suited to take up residence (or expand their reach) in Greenland.

Without help, the researchers’ models indicate that some species of trees would take around 2,000 years to find their way to a newly hospitable patch of Greenland soil. But with tourism and regular flights between continents, the plants will most likely receive some significant accidental colonization assistance. Greenlanders will also most likely start to plant trees themselves, if they believe they could now grow there.

“People often plant utility and ornamental plants where they can grow,” Jens-Christian Svenning, a biologist at Aarhus University, states. “I believe it lies in our human nature.” However, he warns that if Greenland’s greening is left up to the locals, they should proceed with caution.

“The Greenlandic countryside will be far more susceptible to introduced species in the future than it is today,” he said. “So if importing and planting species takes place without any control, this could lead to nature developing in a very chaotic way.”

(function(d,u,ac){var s=d.createElement(‘script’);s.type=’text/javascript’;s.src=’https://a.omappapi.com/app/js/api.min.js’;s.async=true;s.dataset.user=u;s.dataset.campaign=ac;d.getElementsByTagName(‘head’)[0].appendChild(s);})(document,123366,’vsnpdf60wcdcoy9thuof’);

While “more green” might seem like a win for the environment, the possible shift from mossy tundra to towering forest would almost certainly push out some of Greenland’s native plant and animal species.

On the flip side, new trees may help alleviate some of the erosion issues from quickly melting glaciers and could create recreational or economic possibilities, such as sustainable hunting and foraging for wood and wild edible food. Even just recently, the warming of the Arctic environment has allowed new crops like apples, strawberries, broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage and carrots to be grown and for the cultivated areas of the country to be extended.

© Ralph Lee Hopkins

Local Greenlanders are already having to adapt to weather changes. Kaleeraq Mathaeussen, for example, has been fishing since he was 14 years old. Like other locals, he has observed massive changes around him that can’t be ignored. In the past, he used to travel on the ice each winter with a sled pulled by his beloved dogs. But the water no longer freezes like it used to.

“Ever since 2001, I noticed the winter seasons in Disko Bay didn’t have as much ice. I was very worried when I started to notice that the ice barrier was getting weaker. Today it is unpredictable and too dangerous to go fishing with my sled dogs,” he explains.

Mathaeussen stopped sledding two years ago, and now he only feels safe fishing by boat.

And Mathaeussen isn’t alone. Around two decades ago there were around 5,000 dogs in the larger coastal town of Ilulissat alone, but now there are only about 1,800, as many Greenlanders give up this traditional transportation method.

“There’s some negative things. There are also some positive things,” Mathaeussen states. He explains that in some ways, Arctic life has become easier. For instance, nutrients from glacial meltwater are enriching marine life, and with the warmer weather, it’s now possible to fish year-round by boat. Halibut fetch a high price, and fishermen like Mathaeussen are now financially better off because they can fish for a longer season.

© Ralph Lee Hopkins

With all of these changes happening relatively quickly, the time to visit Greenland is now. On Nat Hab’s East Greenland Arctic Adventure, travelers have the chance to speak to locals firsthand to get their perspective on how climate change is affecting—and will affect—them.

In addition to our time at our Base Camp, we spend time in the tiny village of Tinit, a 20-minute boat ride from camp. Most visitors never get to these remote communities, but our overnight stays allow us to meet the local Greenlandic Inuit, learn about their culture and traditions, and gain an appreciation for the challenges and rewards of life in a rapidly changing modern Greenland.

Consider an upcoming Nat Hab trip to Greenland as the perfect place to unplug, connect with nature, and see for yourself the impact of climate change in the Arctic.

The post Climate Change Is Making Greenland Greener, But Is It a Good Thing? first appeared on Good Nature Travel Blog.

In part one of our two-part Q&A with Aditya Panda, we discussed the veteran guide’s favorite national parks in India, which wildlife travelers will encounter on an India safari, and what it’s like to track tigers in the wild (we’ll never forget his vivid account).

Here, the passionate conservationist, wildlife photographer and Expedition Leader with Natural Habitat Adventures shares his insights on India’s immense conservation successes—including in Kanha, Bandhavgarh and Kaziranga national parks, all featured on Nat Hab’s Grand India Wildlife Adventure—the imperative of ecotourism, and the pivotal role travelers can play in preserving India’s wild places.

Kanha brought back the hard-ground swamp deer (barasingha) from the brink of extinction. They were down to 66 in 1970. Today, nearly a thousand barasingha adorn the meadows of Kanha, and about 100 have been reintroduced to form a second “insurance” population at Satpura Tiger Reserve, 300 miles away.

Bandhavgarh lost its entire population of gaur (India bison) in the 1990s. The species was reintroduced in the following decade and now the world’s largest wild bovine is well established there again. Both these reserves are flagships of India’s tiger conservation efforts and are home to some of the largest breeding populations of tigers.

Kaziranga has seen a century of conservation. The greater one-horned rhinoceros is one of the best conservation success stories of the 20th century, and Kaziranga single-handedly deserves credit for that. These reserves have consistently exhibited the strongest protection approaches and well-managed tourism practices that directly benefit conservation.

India is the world’s second-most populous country and is extremely land-starved. Holding aside land for wildlife is an inherently conflicted matter. High rates of infrastructural growth and increasing urbanization mean that wildlife landscapes are fragmented. Large mammals are usually wide-ranging creatures and require unhindered right of way through natural landscapes across vast distances.

There are also threats from extractive livelihood practices. Grazing livestock in wildlife habitats not only causes deer and wild ungulates to be outcompeted for forage, but it also brings in the risk of communicable diseases to wildlife. Predation of livestock by tigers and leopards causes human-wildlife conflict. The collection of forest products such as firewood, fruit and resins also causes habitat deterioration, forest fires and human-wildlife conflict. And the threat of poaching always exists. This can range from snaring and bushmeat hunting that depletes prey base for large carnivores to the poaching of tigers, leopards, Asian elephants and one-horned rhinoceros for the international trade in wild animal parts.

Fortunately, the nature parks we visit on the Grand India Wildlife Adventure are living examples of how these challenges to wildlife conservation can be effectively managed. That’s why they’re such rich repositories of wildlife, enabling us to enjoy and learn about these beautiful animals and their habitats that we so love.

Yes. It is absolutely essential. It’s no coincidence that the most famous reserves on India safari itineraries are the ones that have consistently shown best conservation practices and wildlife population growth.

The most important way in which ecotourism benefits conservation is that it offers local communities a more positive way to interact with surrounding habitats. With shrinking forests and exponential growth in human population, resource-extractive livelihood practices are no longer sustainable for communities that live around forests. Ecotourism offers much better and safer livelihoods. The best thing is that these opportunities occur at scale, benefitting many villages, and aren’t token. Jobs include park guides, jeep drivers and owners, lodge staff, suppliers and owners, and many wildlife tourism entrepreneurs. The opportunities are endless.

Ecotourism also earns direct revenues for the reserves, providing large amounts of liquid funds used to address human-wildlife conflicts, hire additional protection and fund research. What’s more, travelers on an India safari serve as additional eyes that not only keep away poachers and timber smugglers but also help monitor the state of our reserves.

The most long-term impact of ecotourism, though, is the goodwill it builds for wildlife in the hearts of people. Indian wildlife reserves are visited not just by overseas visitors but also a very large proportion of domestic travelers. These ecotourists not only educate themselves about the natural world but also become more aware of it, and this, in turn, helps build a better society that values wildlife and wild spaces.

The single most important thing that a prospective ecotourist can do is to find a responsible, ethical travel company with a strong background in sustainable travel. This will automatically ensure that at every stage of their journey, the company will strive toward carbon neutrality, responsible practices, meaningful conservation education and a meaningful nature experience.

As a Nat Hab Expedition Leader, I deeply love what I do. Combined with the kind of wilderness experience visitors enjoy here, the magnetic charm of the tiger, the heartwarming sight of elephant families, it’s only natural that my passion rubs off on them, and they turn into ambassadors for India’s wildlife. Because thousands of livelihoods depend upon guests, one of the best things travelers can do when they return home is to encourage others to visit high conservation-value destinations like Bandhavgarh, Kanha and Kaziranga.

Public discourse has always played a great influence on conservation policies. The opinions that international travelers provide—be it directly to the park management, local governments or even their own governments—along with what’s discussed on social media always play a big role in drawing attention to conservation issues. Something as simple as guests providing a slideshow from their Grand India Wildlife Adventure at a local club or community center can trigger interest and awareness about wildlife conservation in India. Last, but not least, by traveling with Nat Hab, you’re also contributing to World Wildlife Fund‘s global conservation efforts.

The post Conservation Success Stories from India’s National Parks first appeared on Good Nature Travel Blog.

By Bas Huijbregts, WWF African Species Director for the Wildlife Conservation Program, and Jake Sokol, WWF Senior Director of Philanthropy of the Eastern Region

“Look at that strange rock!” one of our guests proclaimed upon arrival at our first lodge on Impalila Island, a secluded treasure tucked away in Namibia’s Zambezi region, on the border of Botswana’s Chobe National Park.

© Bas Huijbregts / WWF-US

It was a perfectly camouflaged treefrog, hidden on the trunk of a 600-year-old baobab tree. It was our first wildlife check during our travels across three Southern African countries within the Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA), a place like no other on Earth.

Through scenic flights, 4×4 safari trucks and aboard the Zimbabwean Dream, a beautiful ship built for Lake Kariba, we saw how WWF is working with communities, conservation partners, governments, and the private sector to protect KAZA’s iconic wildlife and their habitat and support the socioeconomic well-being of local communities. We visited four diverse national parks, including Zimbabwe’s famous Hwange and Botswana’s Chobe, and concluded in spectacular Victoria Falls on the majestic Zambezi River, one of the world’s largest waterfalls, and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Map of our Southern Africa Odyssey

In 2011, KAZA’s five member countries—Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe—signed a Treaty to collectively manage a transboundary conservation landscape larger than California in an initiative that ranks among the world’s most ambitious conservation endeavors. Spanning the Zambezi and Okavango River systems, the landscape’s woodlands, wetlands, and grasslands provide continuous habitat not only for our frog, but also for over 600 bird species, 25% of the world’s wild dog population, 20% of the world’s lions, 15% of the world’s cheetahs, and many, many elephants.

KAZA holds the planet’s largest connected population of elephants, enabling them to move across borders and between protected areas. In 2022, the KAZA countries, supported by WWF, undertook the first-ever coordinated and synchronized elephant survey of the entire landscape. Following 195 flights over 2 months, using 7 aircraft, and having flown 1.8 times the Earth’s circumference, elephant experts estimated that KAZA holds a staggering 227,900 African savanna elephants, over 50% of the total population of this species. And wherever we went, from Chobe National Park in Botswana to Matusadona on the southern shores of Lake Kariba and Hwange National Parks in Zimbabwe, we met them. Everywhere. But in these semi-arid landscapes we also saw the impact that these majestic animals have on the landscape.

In 2024, following an exceptionally poor rainy season, triggering drought conditions throughout the region, four of the five KAZA countries (Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe) declared a State of Emergency due to the drought. Elephants need between 30-50 gallons of water per day for drinking, in addition to bathing and playing. This influences their daily activities, reproduction, and migration, and can lead to human-elephant conflict. To prevent elephants from leaving protected areas in search of water in human settlements, most protected areas in KAZA have installed artificial water sources, especially near tourism lodges.

Artificial waterhole, Davison’s Camp, Hangwe National Park © Bas Huijbregts / WWF-US

All those thirsty elephants dominate the waterholes, chasing off other species. With no other sources of water available to them in the dry season, the elephants also stay near these water points, overexploiting the surrounding ecosystems.

Elephant movements in KAZA are further restricted by various human barriers. Park fences, erected to keep dangerous wildlife in and poachers out, limit elephant movements. Veterinary fences, erected to separate wildlife from cattle to avoid disease transmission, have also fragmented the landscape. KAZA’s elephants also need to share the landscape with 2,5 million people, 537,000 cows, and 174,000 sheep and goats. Finally, historically large-scale elephant poaching in parts of KAZA, such as during the civil war in Angola, has further contributed to the uneven distribution of elephants across the landscape. For instance, Botswana’s part of KAZA holds about 132,000 elephants, whereas in Angola, only 5,983 elephants were counted during the KAZA elephant survey.

And here lies the challenge: In places where elephant numbers are increasing in KAZA, they pose a threat to diminishing riverine and woodland habitats and the species dependent upon such habitats. Also, increasing elephant populations, combined with human population growth and human settlements, are leading to increases in human-elephant conflict. This could “push” elephants away from those areas. On the other hand, the KAZA portions of Angola and Zambia have large tracts of suitable elephant habitat, but with smaller populations of elephants and other wildlife (and lower human densities), which could “pull” elephants.

To assure landscape connectivity across KAZA in a changing climate and allow KAZA’s elephants to freely move from densely populated areas to areas with greatly reduced elephant numbers, a Strategic Planning Framework for the Conservation and Management of Elephants in KAZA was developed and endorsed by the partner states in 2019 with as its vision: “KAZA’s elephants, the largest viable and contiguous population in Africa, are conserved to the benefit of people and nature within a diverse and productive landscape”.

Important progress has been made since then. Because of the KAZA elephant survey, we now have accurate information on elephant numbers and their spatial distribution across the landscape. In addition, and based on analysis of 3.9 million GPS observations from 291 collared elephants, we have also been able to map elephant movements across KAZA over the last decade or so, which resulted in the identification of the most prevalent movement routes and elephant corridors.

Those (transboundary) elephant movement corridors are in various stages of intactness and face the potential threat of permanent closure due to encroaching human settlements, agriculture and infrastructure developments (e.g. roads, rail), livestock disease control measures (veterinary cordon fences), and potential mining developments.

Securing and connecting (or re-connecting) these corridors for elephants across KAZA is our collective crucially important mission for the coming years.

The post Elephants Everywhere, But Where Has the Water Gone? first appeared on Good Nature Travel Blog.